For the modern tourist, art is just one among many inducements to visit Italy, and though the Vatican galleries and the Uffizi in Florence certainly figure on every tourist’s “Must See” list, nowadays gallery-going must compete with food, fashion, shopping, and the pleasures of watching street life from a terrazza di caffè.

Early 19th century travellers (the word ‘tourist’ wasn’t yet in general usage) only mentioned the food if it was bad and they weren’t in Italy to shop, unless they were wealthy enough to acquire some piece of Roman antiquity or a minor Italian master. They were there above all to look at art. The conditions under which they saw it were in some ways far pleasanter than those art-lovers endure today. True, they might have to hold a perfumed handkerchief to their nose as they climbed the steps to the entrance. But there were no queues, no crowds and, above all, no selfie-takers blocking the view (though there might be artists at their easels making copies of particular masterpieces). The selfie or égo-portrait (as the Quebecois say) was not yet conceivable, though if you wanted a record of your trip there were artists (like Monsieur Ingres in Rome) who would produce a charming pencil sketch against a suitable background.

Or, if you were wealthy enough, one of Signor Pompeo Batoni’s successors would create a life-size portrait to hang in your drawing-room, like this picture of a young Englishman in Rome, map in hand leaning nonchalantly against a piece of (probably fake) antiquity

But most travellers weren’t looking for a flattering portrait of themselves to take home, though the idealised human image featured prominently in the art they’d come to see, from the sacred figures of Christian iconography to the divinities of Greek and Roman mythology. What made them endure the discomforts of the long journey and the sometimes primitive conditions of the inns was the thrill of seeing a Raphael or a Michelangelo, and a host of painters such as Guido Reni or Domenichino who have fallen from favour today.

Looking back from the image-saturated environment of the 21st century it’s hard for us to imagine the impact on the early 19th century traveller of Italy’s extraordinary artistic wealth. Even Henri Beyle, one of whose duties as inspector of Napoleon’s palaces was to supervise the inventory of the Musée Napoléon [the Louvre], felt overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of artworks in churches, galleries, and the private collections of the nobility. At least in the more intimate setting of the latter (as he discovered at the Bologna residence of Count Marescalchi), distraction is to be found since it’s permissible to introduce oneself to a stranger (as one might talk to another guest at a reception). With a question or a witty comment about the art, an elegantly dressed Frenchman with polished manners (as Beyle flattered himself he was) might safely approach a woman whose expressive Italian eyes revealed the impression he’d made [diary, 24 September, 1811]. How much better to view art in the company of an agreeable woman than be dragged from picture to picture by a tedious guide who insists on showing you everything.

At the newly opened Brera gallery in Milan (one of Napoleon’s creations), Henri Beyle is most taken by Guercino’s ‘Abraham repudiating Hagar’, partly because Mme Pietragrua (his current flame) admires it.

Later, viewing it alone, without Angela’s distracting presence, he recognises the psychological truth in Guercino’s portrayal of a rejected mistress. What he looks for in art, he’s coming to realise, is the expression of complex emotion and truth to nature, but most of the paintings he sees in Italian galleries seem disappointingly bland and conventional.

In Florence, he’s dissatisfied with everything except for Bronzino’s ‘Christ’s descent into Limbo’, which he finds more beautiful than anything he’s ever seen. A predictable reaction, perhaps, in a man who’s admitted to his diary that he needs beautiful bodies and faces in art if he’s to respond to it. Yet there’s something beyond this painting’s erotic appeal that moves him almost to tears. He’s an atheist, so it’s not the religious meaning that moves him but perhaps the universal longing for reunion with loved ones after death.

The Wikimedia Commons site for this crowded canvas offers many enlarged details and identifies many of the figures from the Old Testament portrayed there.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Firenze_(6276569209)

ho visto nina volare from Italy https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jere7my/4107826341

Bronzino’s ‘Limbo’ and the Raphael rooms at the Vatican (which Henri tells his sister he would ‘sell his shirt to see again’) http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/stanze-di-raffaello.html are the artistic highlights of Henri’s Italian tour. He makes no mention in his diary of Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sistine Chapel. Perhaps, being shortsighted, he simply couldn’t see them well enough. He’d already remarked in Santa Croce that ceilings were beyond the reach of his weak eyes, so the 13.4 metre [44ft.] high ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (with the sublime Creation of Adam) would have been lost on him, particularly since it was obscured by three centuries of candle grease and soot. (To get a sense of this, look at the before and after pictures in Wikipedia’s article on the recent cleaning and restoration.) As for the more easily viewable ‘Last Judgement’ above the altar, his History of Painting in Italy (1817) discusses it at length, but he probably didn’t see it until his later, more extended stay in Rome (December-February 1816-17).

All Marie de Vernet had seen of art before her journey to Italy was a volume of black and white engravings of famous paintings. Consequently, on first entering the Brera Gallery, she is dazzled by colour ‘like a blind person whose sight has been restored’. Her guide, Jean-Philippe Larocque, is an old acquaintance of her cousin’s who has kindly offered to show her round Milan. Ill at ease with a stranger and embarrassed by her ignorance of art, Marie fastens her eyes on the nearest painting, drawn by the delicate landscape in the background.

It’s Cima da Conegliano’s St Peter Martyr with Saints Nicholas and Benedict. View it at https://pinacotecabrera.org/collezione-online/opere/san-pietro-martire and you should be able to enlarge the landscape details that charmed Marie.

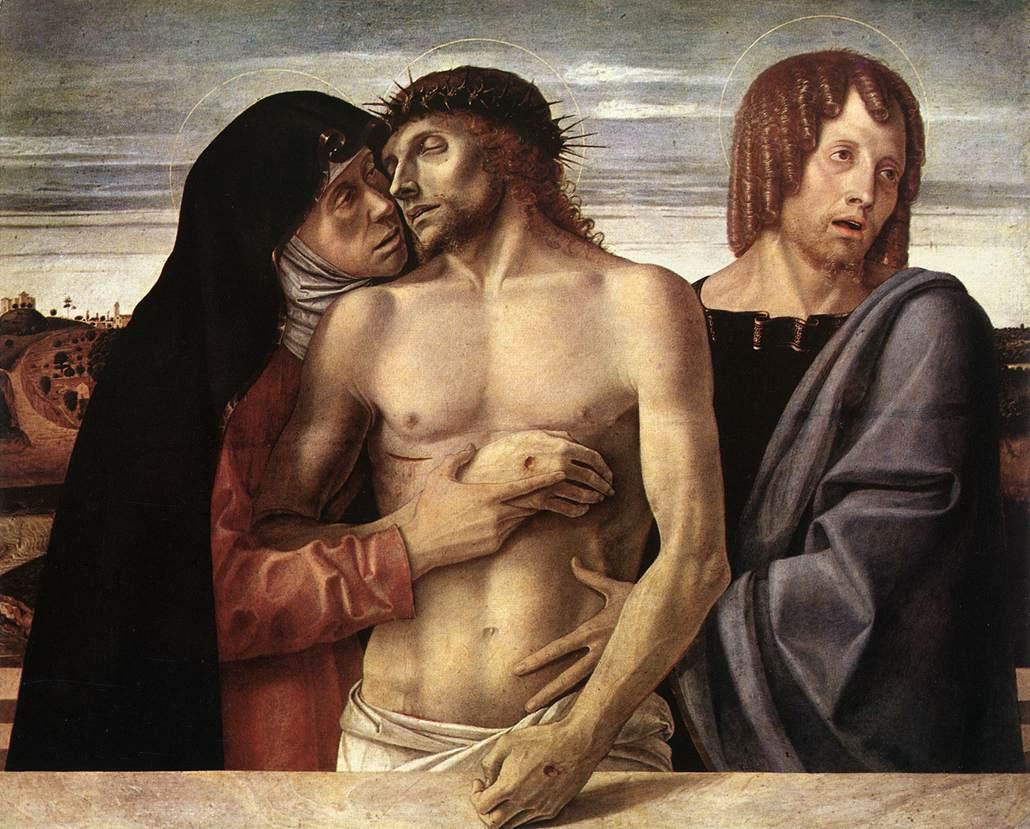

Larocque shows her the painting that means most to him — Giovanni Bellini’s Pietà — and confides what it means to him as a non-religious man, all too familiar with death and mourning. http://pinacotecabrera.org/collezione-online/opere/pieta-giovanni-bellini

Two shy individuals like Marie de Vernet and Jean-Philippe Larocque could reveal themselves in front of paintings that stirred their deepest feelings. And a gallery, with a cicerone or a custodian hovering in the background, was a respectable place for a single man and woman to be seen together (though there might be gossip if you were seen deep in conversation unattended by a guide). Over the next few weeks, as they slowly become better acquainted, they will look at many paintings together, seeking out those with background landscapes.

Here is a selection of what they look at.

This lovely image of the Madonna and Child against a background of farms and fields is one of Marie’s favourites, which she returns to again and again. It’s the painting that she is trying to imprint on her memory when she’s approached by Henri, who has been struck by her intense concentration and recognizes her as the woman in grey from the diligence (p. 273).

And here below is the painting of the Madonna and Child with Four Saints by Crivelli on which Henri exercises his wit (p. 268). Look at the full screen version online to see if you can spot the crack on the edge of the dais on which the Madonna’s throne stands, which puzzles Marie.

Finally, here are the two paintings that Marie spends time with in Larocque’s absence. She is very struck by the image of the veiled women in the picture of St Mark preaching in a square of Alexandria by Gentile Bellini (completed by his brother Giovanni after Gentile’s death).

https://pinacotecabrera.org/collezione-online/opere/saint-mark-preaching

View online to enlarge details. This is, of course, not the Alexandria of the first century CE where the evangelist Mark preached but the fifteenth-century city of Mamluk Egypt which Gentile Bellini may have visited.

Marie spends two afternoons with Raphael’s Betrothal of the Virgin, wondering why it leaves her unmoved, since at this time Raphael is generally considered the greatest of Italian painters.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Marriage_of_the_Virgin_(Raphael)

You will find Marie’s reflections about the Raphael on pp.247-248 and 254-255 of the novel.

Before the era of colour reproduction, art-lovers had no means of enjoying their favourite paintings once they’d left Italy, whereas the modern traveller has only to take a photograph or turn to the internet for full colour images that can be enlarged on the screen with every detail magnified at will. Marie’s attempt to imprint the image of Bellini’s Madonna and Child on her mind and carry it with her in memory when she leaves seems a poor substitute. And yet I sometimes wonder when I see people hurrying through a gallery smartphone at the ready what they actually see when they spend so little time looking.

Is Marie’s attentive gaze a capacity that has been lost or seriously diminished with the advent of modern media?

Wonderful to have my own guided tour among the paintings that are so central to the emotional life of your novel–wonderful both for seeing and for the history you provide and the speculation: Henri was maybe too shortsighted to appreciate the Sistine Chapel! Of course!

Glad you enjoyed the tour, Susanna. With respect to Henri’s shortsightedness (literal and figurative), I’ve added a further explanation to the mention of the Sistine Chapel. In today’s viewing conditions, it’s hard to imagine just how difficult it was to view Michelangelo’s frescos in 1811.